Decade Memoir #7: Bryan Vitale - Fallout: New Vegas

The year 2010 seems like just yesterday, but a decade is a heck of a long time. Around this time ten years ago, Dragon Age -- as a series -- was in its infancy, PAX East hadn't debuted, and the PS Vita had yet to resonate with the underdog in all of us. The psychology of time perception is a bit out of scope for a Game of the Decade feature, but at the same time it feels is oddly appropriate -- where did all that time go, anyway? Who was I ten years ago, and who am I now?

When weighing my inflated nostalgia for video games from my undergrad years against the more immediate recollection of titles that I've written about on this website, narrowing it down to a singular, "most important" experience seems impossible. Every choice felt wrong. When deciding between some of my favorite games from the last ten years, I find myself over-scrutinizing every option. Did that game really mean so much to me -- did that other one really matter?

After wringing my hands while choosing between imperfect game and imperfect game, I ended up invariably returning to Fallout: New Vegas as the game from the last ten years that has most wholly stuck with me as we head into 2020.

Fallout: New Vegas released on October 19, 2010, just eeking into eligibility for a Game of the Decade selection. An auspicious circumstance for me, as it would have been extra difficult to have picked some other, more imperfect game if the decade had aligned just a bit differently. As it happens, New Vegas would end up being one of the last games I would wind up playing in my birth state, before packing everything up and moving away to start a new life in grad school over 1000 miles away.

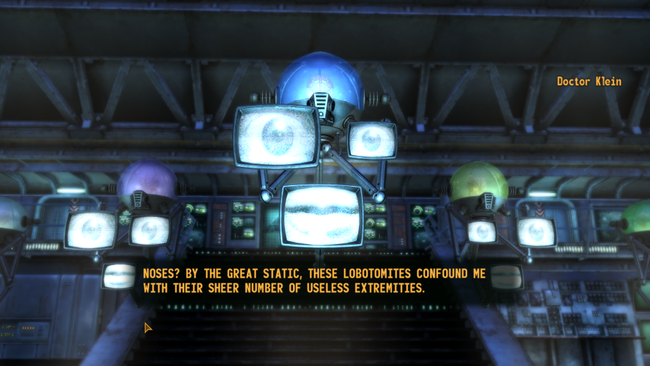

New Vegas is not a great looking game, it never was. It doesn't outwardly do anything new or exciting, existing almost as a full-scale mod to Fallout 3 and appropriately titled like a spin-off. Playing it on modern computers is an exercise in crashing to desktop without some careful modding consideration. Already I feel my zealous over-scrutiny of the game almost undermining the selection outright. But it’s still undeniably my Game of the Decade.

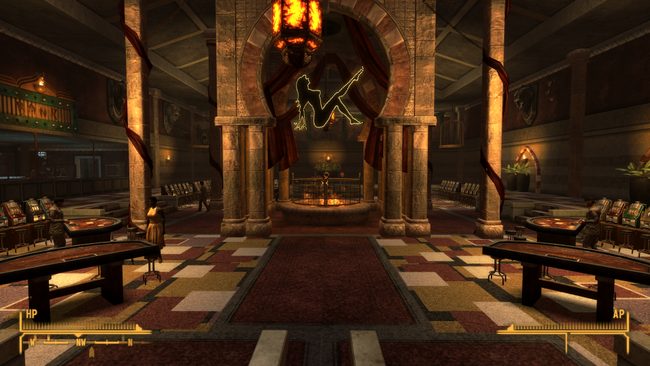

After waking up following a botched murder attempt, the New Vegas player-character, one of the most fitting uses of that hyphenation, finds themselves at the mercy of their own whims. An early questline will point out locations like Primm and eventually the faded neon of New Vegas itself, but outside of this nudging, there's no set path. Even the player, acting as 'The Courier', doesn't really have an overt set history -- none of that really matters outside of the personal motivation to find out why you were left for dead in a shallow grave anyway. The fact that I feel no hesitation in using "you" here is partially indicative of why New Vegas has so strongly stuck with me nearly ten years later.

When I walked onto campus in mid-2011 to kick off the next phase in my life, no one really knew or cared about where I was from. Not because it was some big secret or because I refused to share it, but mostly because it wasn’t something that altogether mattered. I didn’t have to be ‘Bryan from Iowa’, I could just be Bryan. Perhaps not a unique experience outright -- anyone attending university away from home could certainly attest to similar feelings. I guess I was hesitant though, waiting until my second degree to branch away from a history largely decided for me.

New Vegas was one of the first games that I had played that shared this sort of mindset. A series plot summary might conveniently swap out 'The Courier' for the 'Lone Wanderer' or whatever appropriate generic title, but the distinction in title alone doesn't quite highlight the difference in tack that New Vegas takes in comparison to Fallout 3 or especially Fallout 4. While the survivors of Vaults 101 and 111 are inevitably tasked to go with or against some manner of 'destiny', New Vegas instead more directly asks the player what they find important -- the Courier as a bespoke written character matters a whole lot less. Their backstory is so wholly unemphasized that discussions about whether or not the Courier actually had amnesia used to be commonplace.

It's nearly impossible to discuss New Vegas in a vacuum. The point of invoking the endless, inevitable comparison to Fallouts 3 and 4 here specifically is not to needlessly rank or shallowly grade the series as if I'm some sort of authority on that matter, but instead to self-reflect and identify exactly why New Vegas, somehow, ended up mattering to me more. Playing as myself -- or an invented fictional representation of myself -- is not a new thing in video games. Games ranging from Dark Souls to Skyrim to Mass Effect and numerous others allow for both character creation and decision-making, but what makes New Vegas different is just how singular the experience remains to me to this day.

Dark Souls has been iterated on numerous times, Mass Effect has a throughline of multiple connected titles, Skyrim is close, but still leans on a 'chosen one' sort of reliance that stands in contrast with the sort of nuanced story-telling that New Vegas challenges the player with.

As such, none of those experiences have remained as uniquely personal or notable to me as New Vegas, as isolated as the Vegas Strip overlooking the Mojave desert. While many other RPGs ask the player to turn a crank in return for delivering their experience, Fallout: New Vegas handed me a mirror instead as it asked me “Who are you?”.

New Vegas doesn't often deal in the grandiose. There's no real overbearing threat that the player is destined to overcome (though that premise is admittedly compromised just a tad on near the end of Lonesome Road), and there's no singular destiny for The Courier. Instead, I was presented with the challenges of tackling competing ideologies and juggling numerous definitions of order, freedom, and justice. Decisions felt purposeful, not specifically because their outcomes were strictly consequential, but because the decisions themselves often asked me, or at least the in-game representation of me, about my own values - instead of just asking me to steer towards a specific outcome.

Robert House's excessive pragmaticism is what kept New Vegas standing upright in the first place, but whose caution and fear leads him to ruling his 'free' city like a tyrannical despot while withering away sight unseen. The New California Republic outwardly declares a manifesto of democracy and stability, but often undermines their own message with corrupt leadership and needless expansion of territory with seemingly endless fighting. Only the slave-owning Caesar's Legion is generally presented as monolithically unredeemable, but even then, carries the echo of founder Joshua Graham's own tortured history as a missionary -- who honestly believes that his work will save people in the eyes of his God.

I think in a way, we’ve all self-reflected about whether we’ve withered away in the comfortable rut of routine, deceived people with an outward image better than we actually deserved, or ended up doing the wrong thing for what we thought were the right reasons. I certainly know I have.

The Courier's companions also wrangle with questioning their individual ideologies, and the player is positioned to impact those decisions alongside their own. Whether it's asking Veronica to remain with her Brotherhood home or abandon it, or determining the best possible outlet for Boone's unending grief, these are decisions that often do not have clear cut 'best case' results -- the toughest ones never do. Ending cards give each of these choices the minimum amount of closure they require, but nothing more than that. Boone's refusal to negotiate with Legion soldiers and Veronica waiting patiently for me at the Brotherhood bunker entrance are more firmly rooted in my memory than the specific outcomes of their individual fates.

And this is why I feel that Fallout: New Vegas remains meaningful to me. The moments from this prior decade that I end up remembering most vividly aren't simply the ones that clearly made me the happiest or the most miserable. That, I suppose, would make too much sense.

Some of the most impactful moments were in retrospect relatively quaint, unassuming things that rippled outward from larger, impactful decisions. Giving my dog whipped cream on the first anniversary of his rescue a year prior, or helping my brother move his furniture out for a new job 1000 miles away -- a moment that mirrored my own experience in 2011. Even just a random evening of going through old video game screenshots with a good friend. These humble memories remain important to me because they emphasized my own personal values, even if those are difficult to strictly measure. They provide a sense of permanence not in who we claim to be, but instead in what we choose to do.

New Vegas, for me, is a moment that refuses to escape my memory -- that modest but somehow significant recollection that persists because it's derived from the intangible strength of my individual experience rather than some rubricked metric of importance or accomplishment. It is my Game of the Decade because its emphasis on the player as both the catalyst and the consequence of their own actions is an appropriate analogy to my own experience in the 2010s. New Vegas doesn’t often ask me to be a hero or a villain, it just asks me to be someone.